Two world firsts: the first sukkah to use 3D printed parts as an integral part of its structure, and the world’s first geodesic sukkah.

Extra, extra, read all about it here.

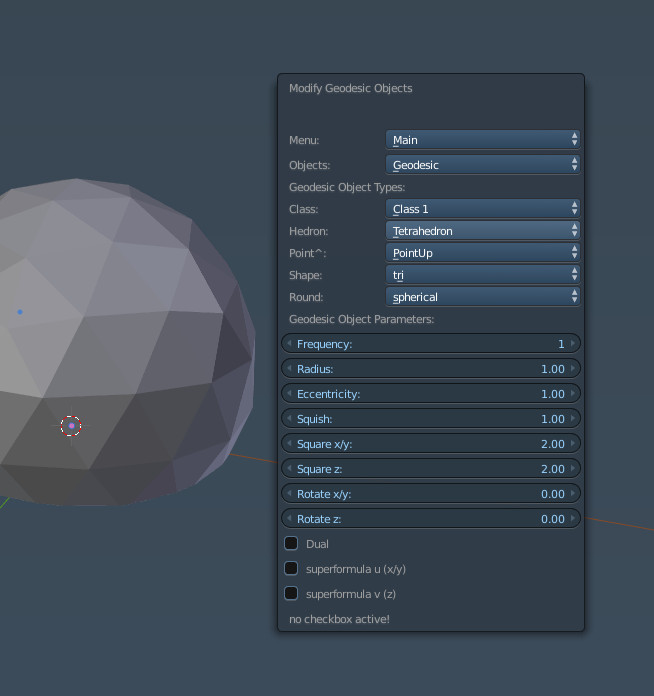

For absolutely ages I have been mulling the idea of building a geodesic sukkah, and never really took the idea too seriously. Oh, I told my kids bedtime stories that featured a geodesic sukkah quite prominently, but after playing around with the geometry in Blender I figured it was simply too much work.

Then my laptop got stolen, I bought a new one and for some reason that sparked my interest yet again in the idea. So I fired up Blender again, did some research and backed off yet again. Ah, but then something clicked somewhere, and I took to the idea quite seriously. Seriously enough to buy some cheap plastic pipe (1 British monies for 2m worth of 22mm overflow pipe) and set about designing the dome.

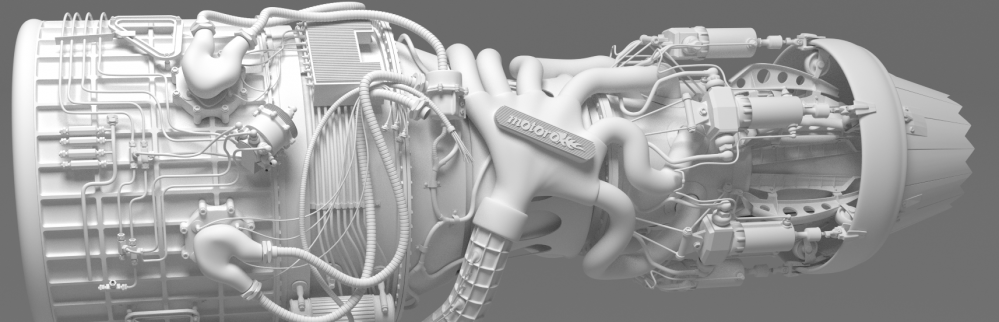

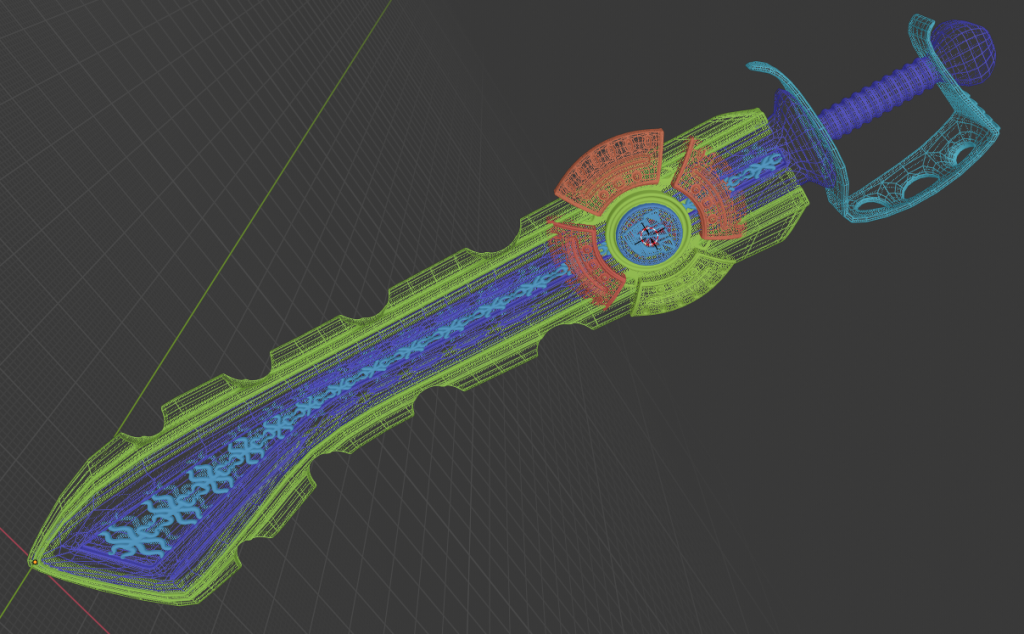

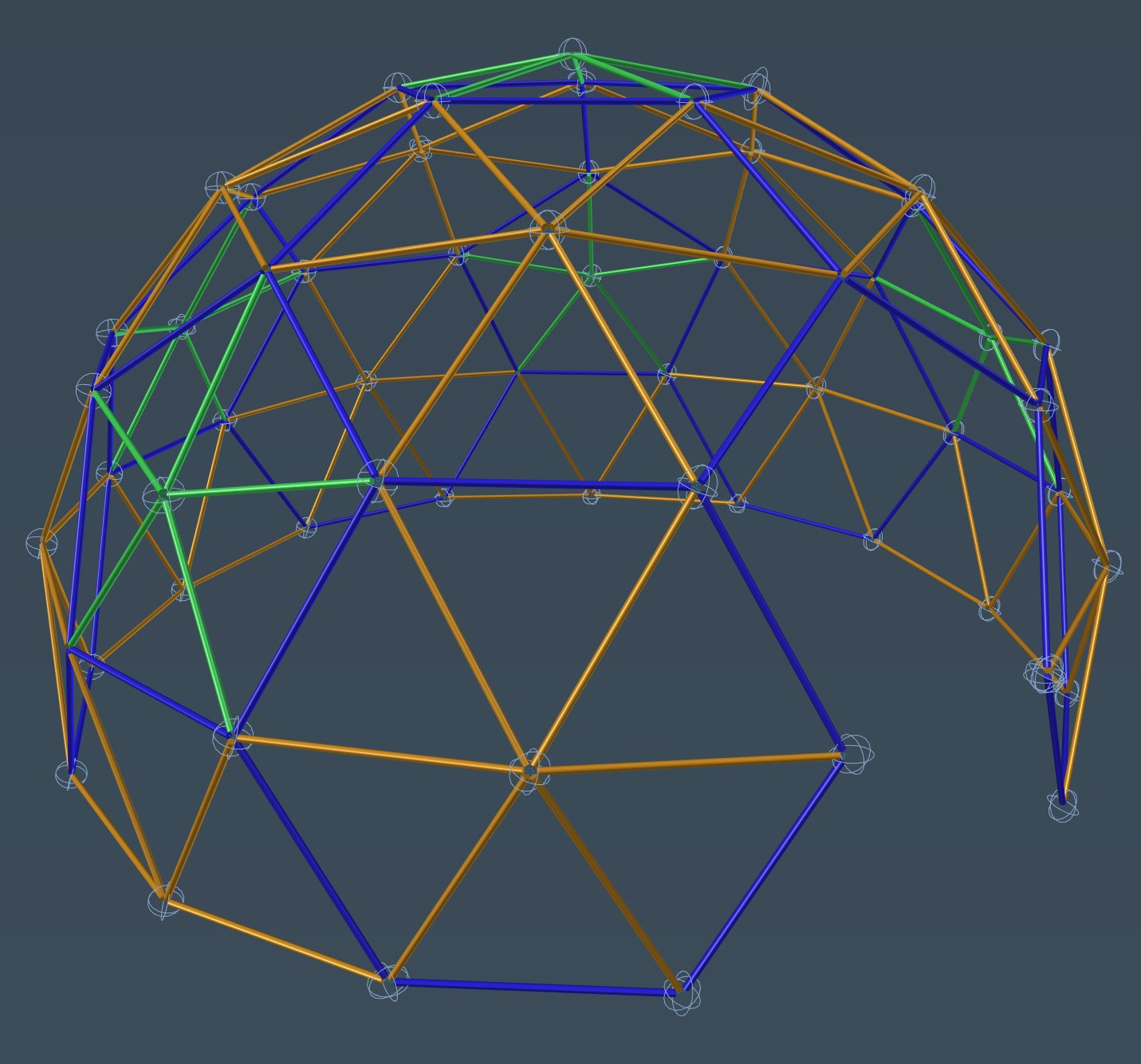

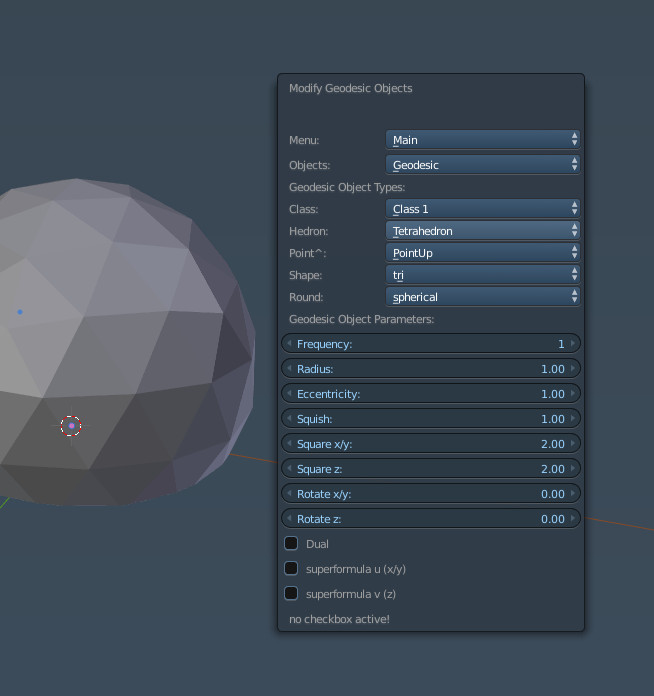

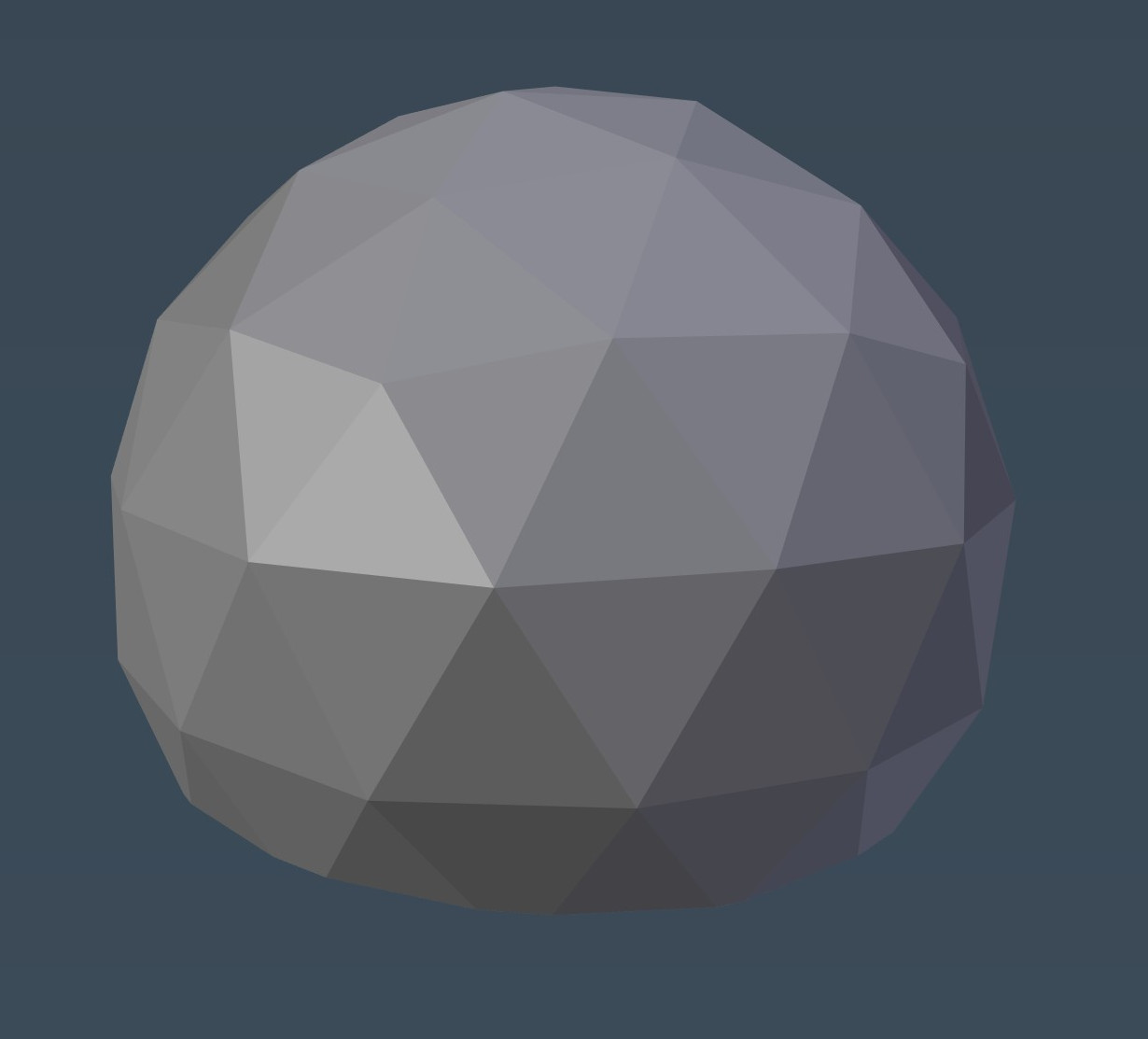

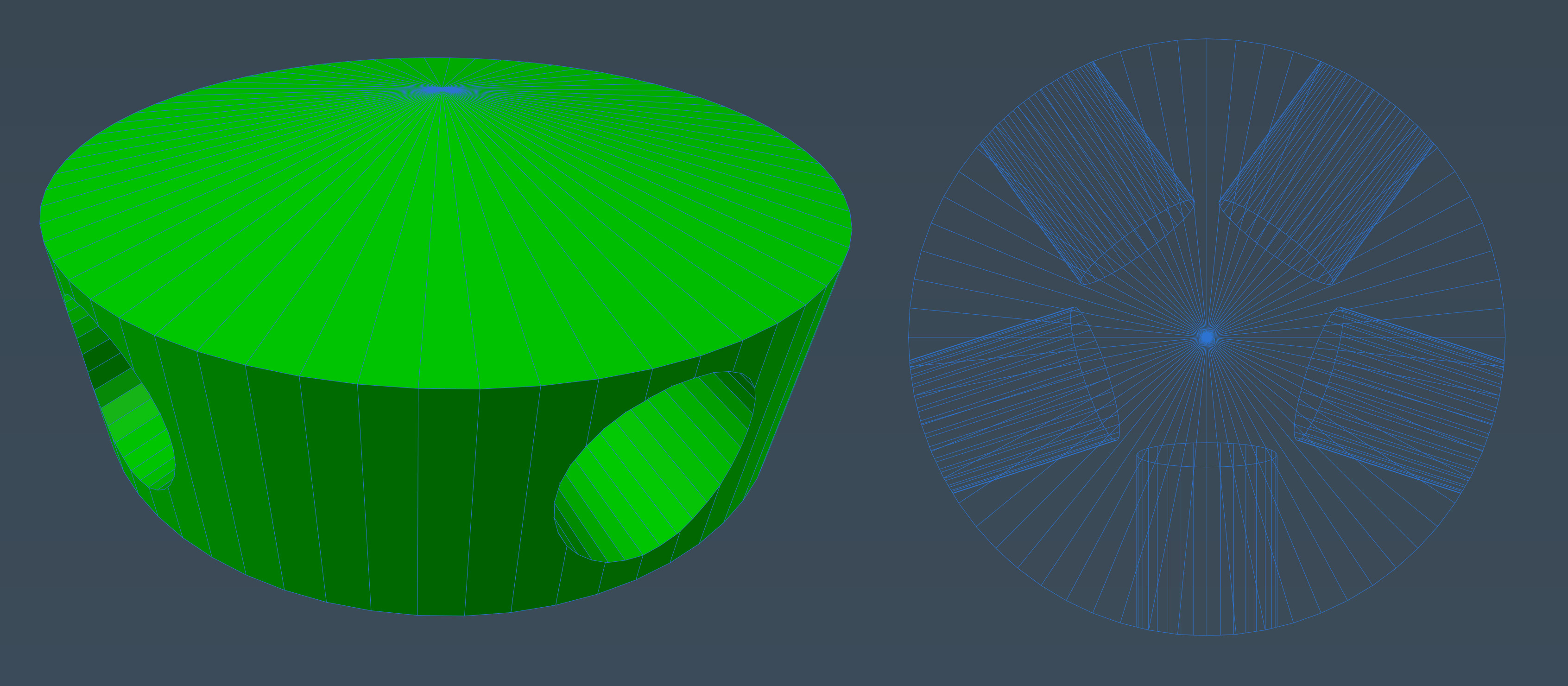

Well, how do you design a geodesic dome altogether? The simplest route is to use the geodesic plug-in for Blender, of course. One click, or actually several hours of fiddling around until the realisation dawned that there is a lot to learn about these kinds of domes, and I had a dome.

Well, sort of. What I had was a geodesic mesh, certainly; but a practical, buildable model it was not. The sheer amount of options was quite overwhelming, and then I had to scratch my head and decide whether I wanted a class 1 or class 2 icosahedron, octahedron or tetrahedron or who knows what. Obviously, I got somewhere in the end.

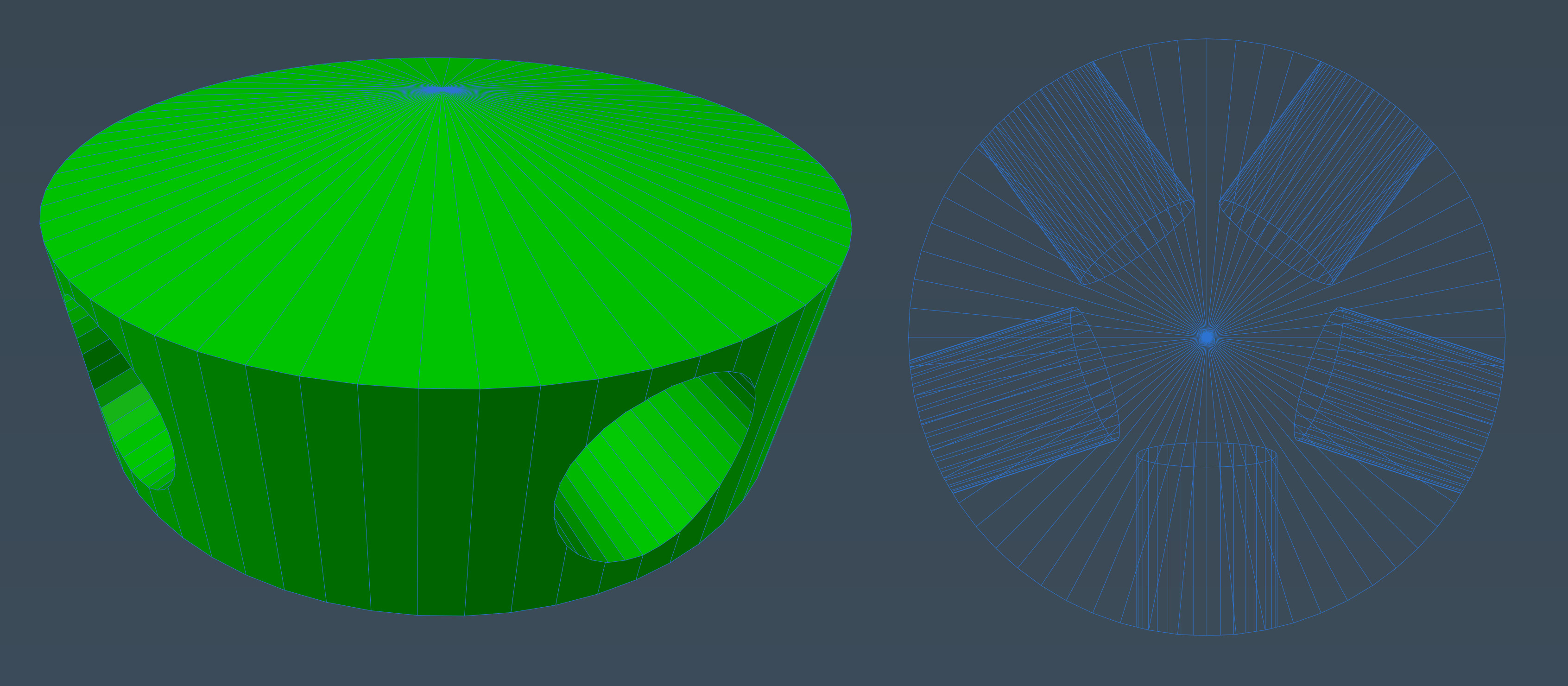

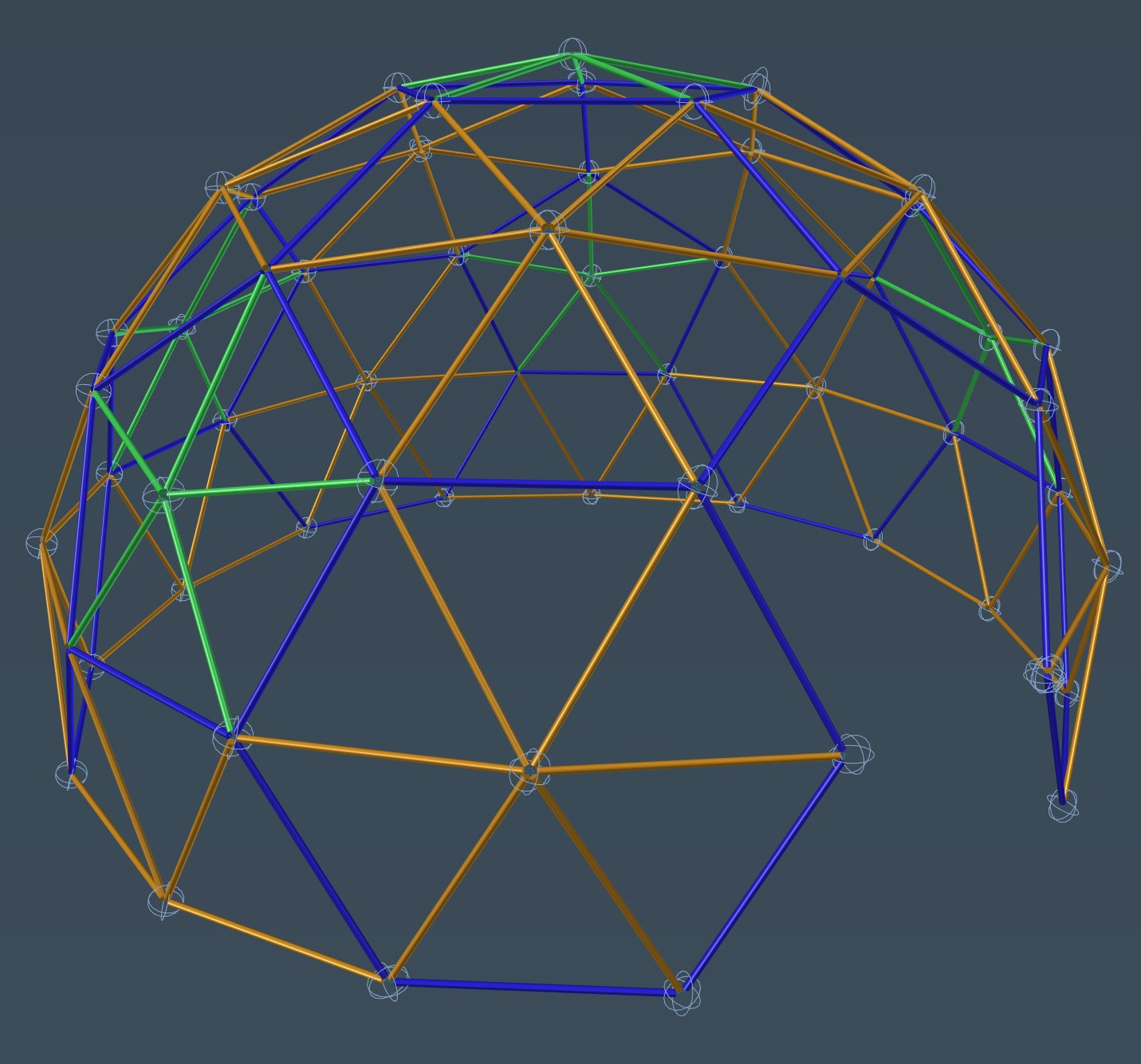

Yet there were more decisions to be made. Ideally I wanted the sukkah to fill up as much space of my garden as possible. I didn’t want the walls to be too shallow, because then much of the usable space would be sacrificed. On the other hand, if the dome was too tall, the base would be too narrow. Ah, choices, choices.

In the end I decided on a maximum diameter of 4.6m, and cut off around 1.3m off the bottom which made for a happy balance.

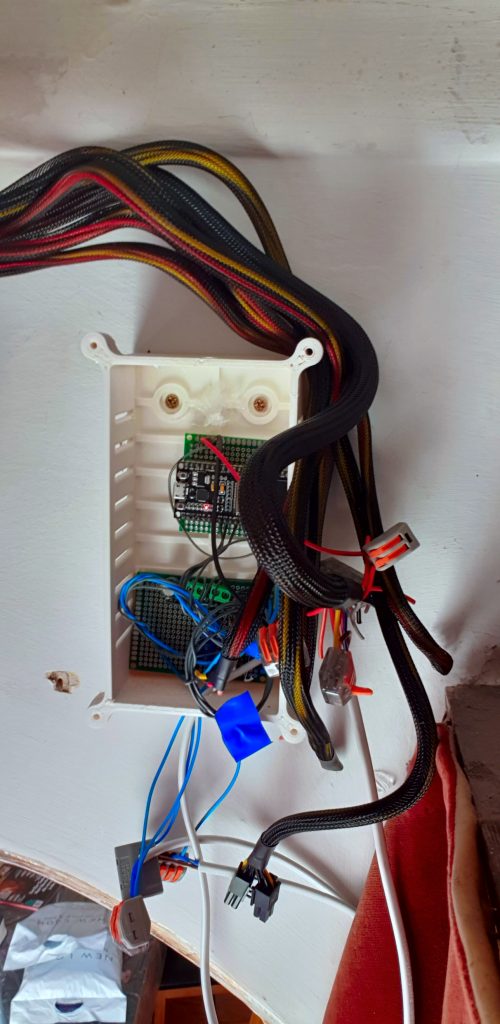

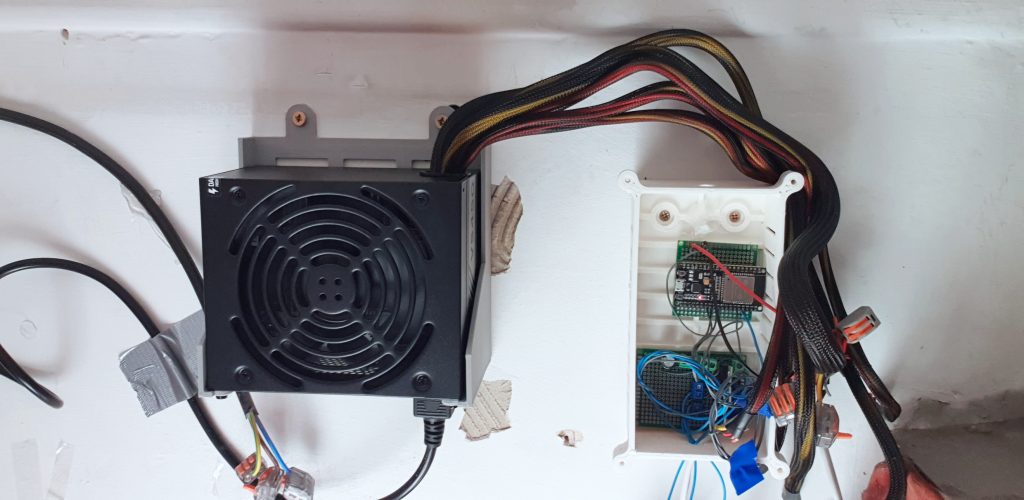

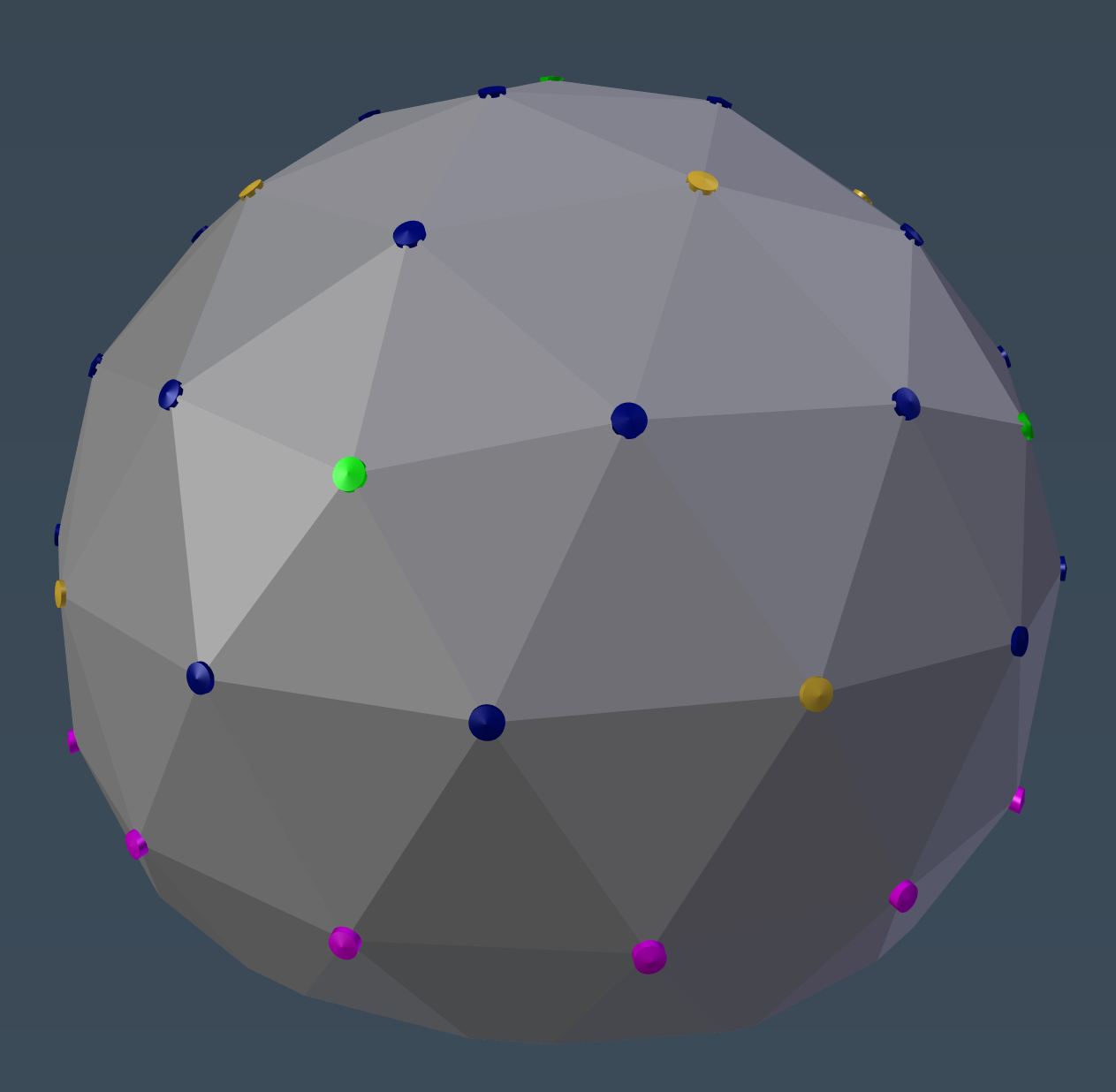

Of course I still had no connectors, and now way of aligning all the connectors automatically, as well as putting the pipes in place and whatnot. All of this required a fair bit of hair pulling and many hot baths.

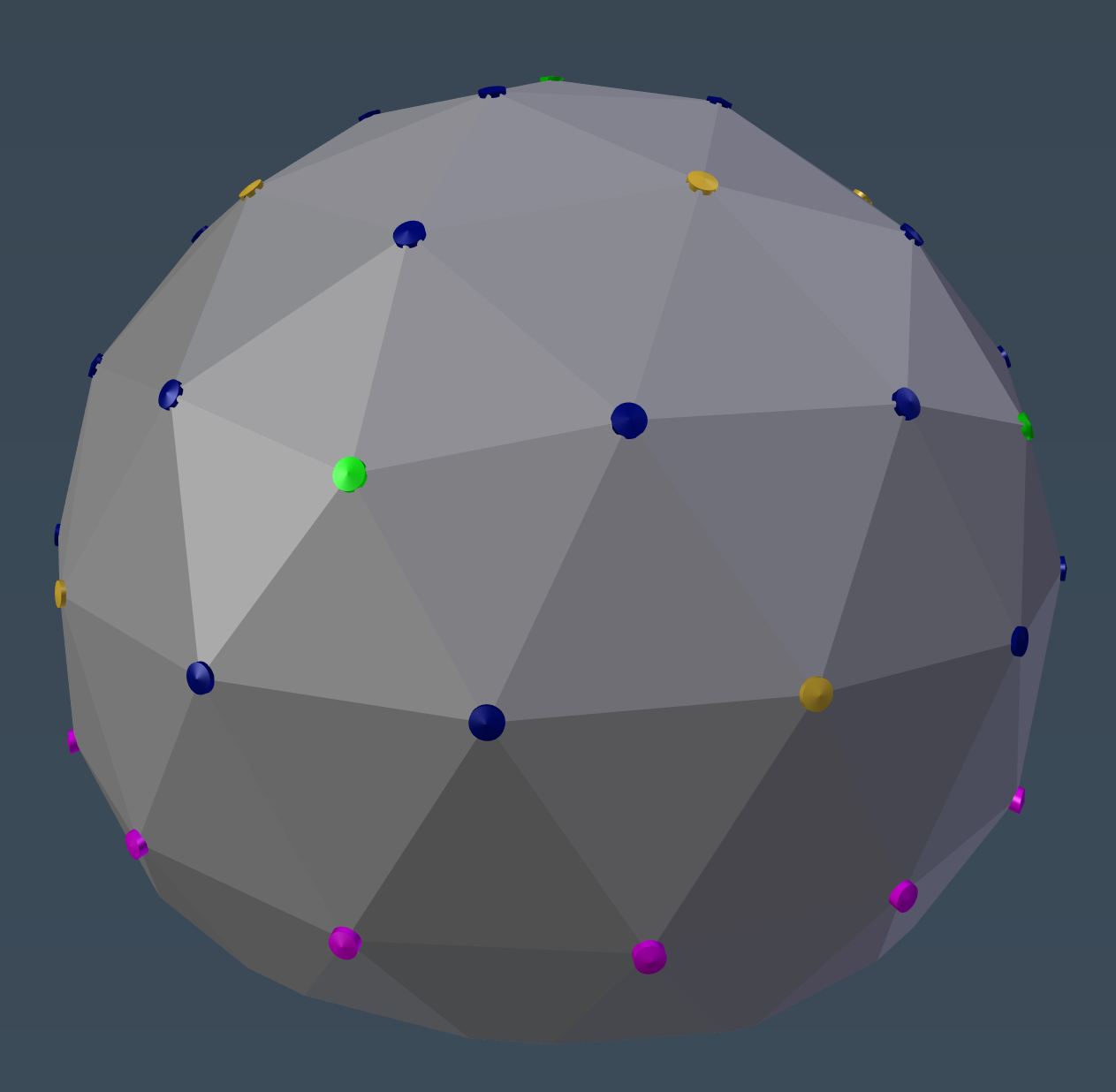

Fortunately Blender has some really powerful tools that came handy, such as the Dupliverts tool. By parenting a mesh to the dome, Dupliverts will stick a copy of the mesh onto each face or vertex, and when using vertices will point the mesh in the direction of the vertex normal. In plain English, you get loads of free copies and everything points to the correct direction. Coolio.

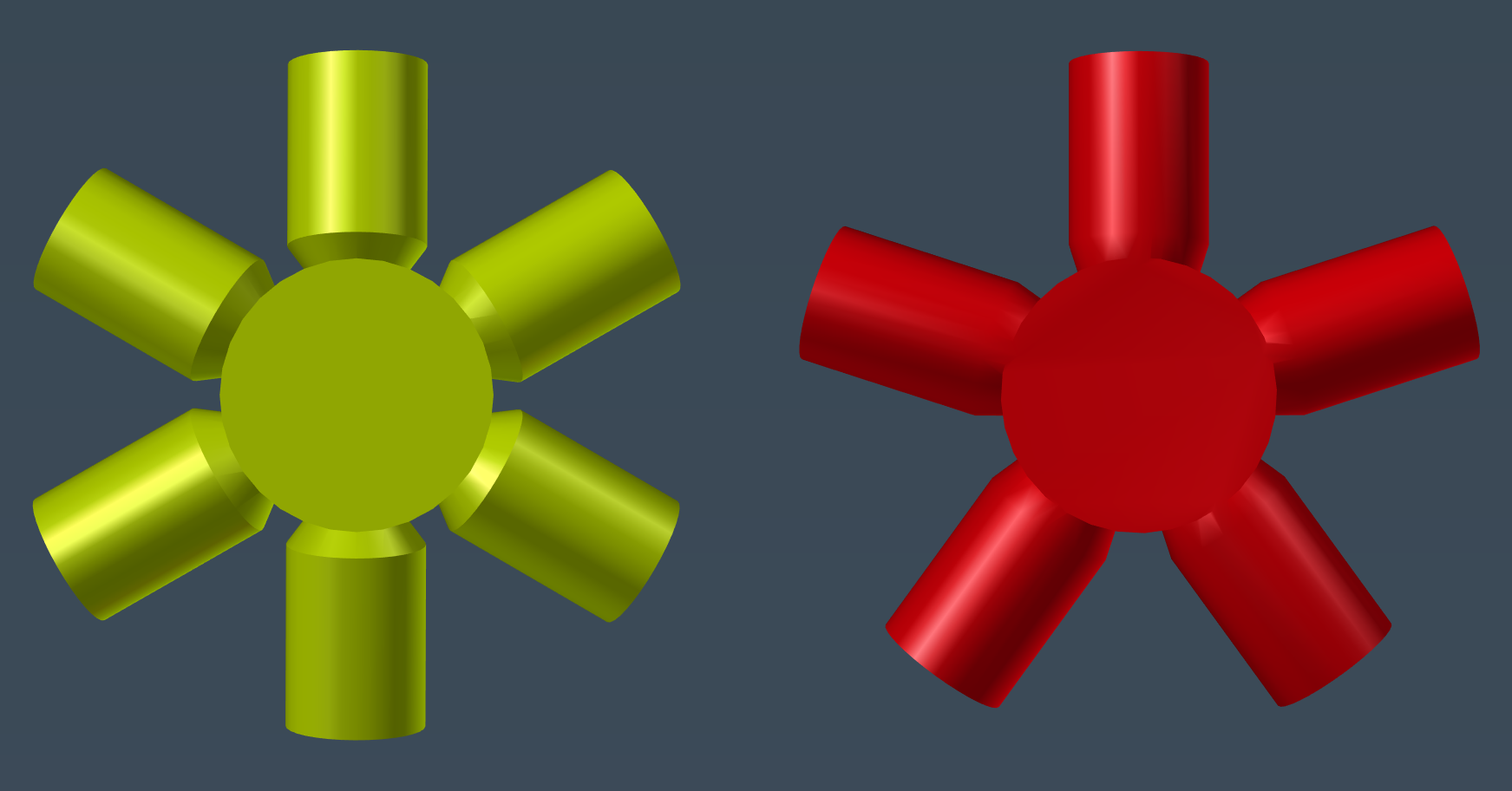

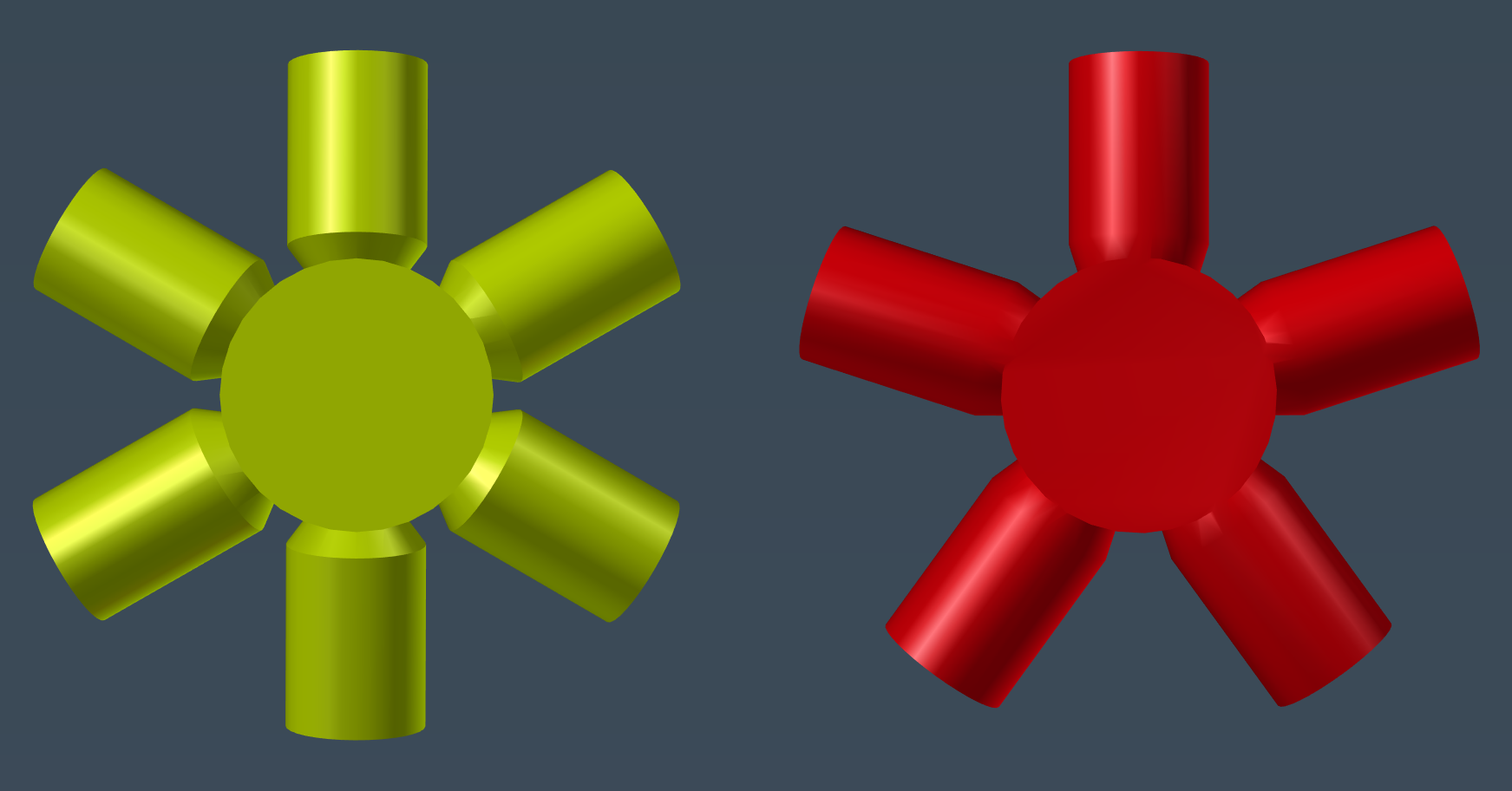

I trolled around the intarwebs to see how everybody else designed their connectors, especially the 3D printed versions, and discovered no-one who had designed an actual working dome using 3D printed parts, and the other connectors that I found were made out of bits of plastic tubing with holes drilled in and cable ties to hold it all together. Mucho too much work for my liking.

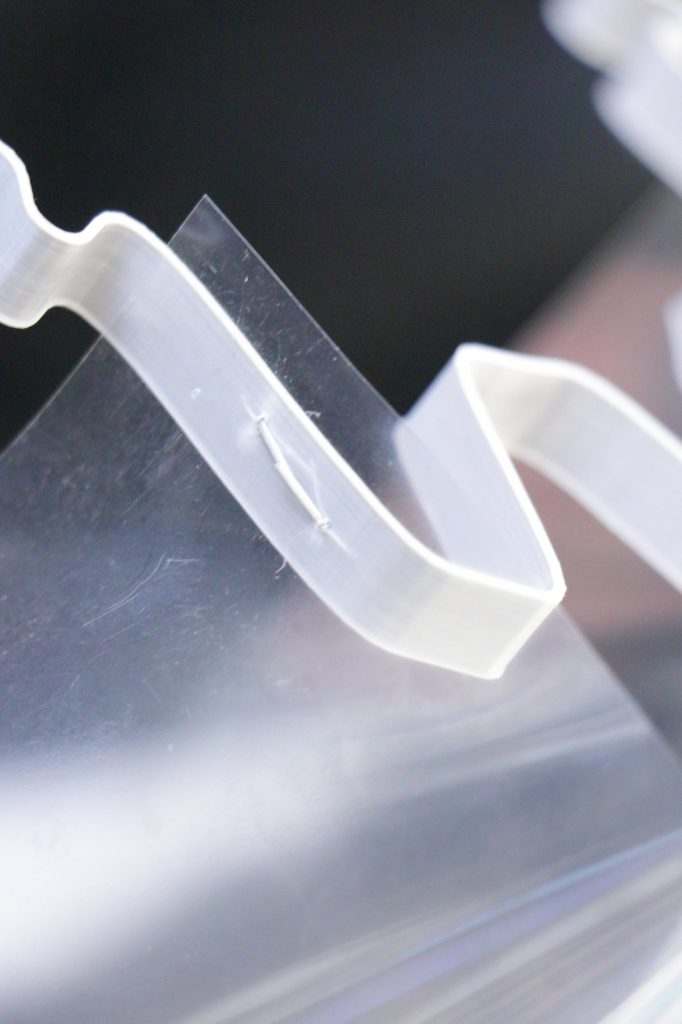

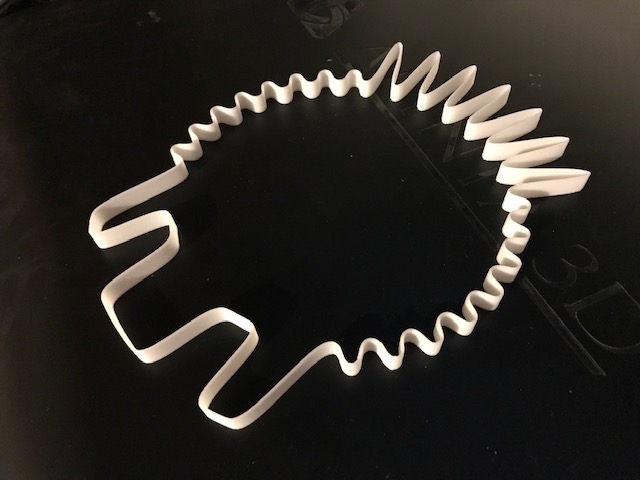

Well, after some cogitation I came up with a fairly clunky but serviceable design, which took 2 hours to print, despite using a 0.8mm nozzle and 0.3mm layer heights.

They were put into service nonetheless in order to test the very top of the dome together with the oh-so-wonderful plastic tubing.

After further cogitation and the dawning of the realisation that Sukkos was fast approaching and I simply did not have the time to print dozens of clunkers, version 2 was developed. It prints in one quarter the time and uses a lot less plastic.

All the parts for the sukkah were printed in ABS, because they were going to be used outdoors and I didn’t want PLA melting in hot sunlight. In hindsight, this was an overly unnecessary precaution, since we rarely get sunlight in this part of the world, and when we do, heat is usually not an issue. Oh well, at least ABS is the cheapest filament I can buy, so all was not futile.

Getting the pipes in place was a bit trickier. What I resorted to in the end was using two empties, one at either end of the pipe, with the pipe parented to one, and tracking the other using a Track To constraint. Then snapping the empties to the desired vertices was simples, and some shuffling along of the pipe was in order to get it into place. Very, very tedious, not technically accurate, but quite effective.

Some stats:

- 180 pipes were cut to length from 100 x 2m lengths

- There were a total of 62 hubs printed

- Approximately 20 metres of cloth was used

- 25 poles were 75.5cm long

- 76 poles were 90cm long

- 54 poles were 88 cm long

- Approximately 400 screws were used

- Something else interesting was going to go here, but I forget what

- Yes, I only listed 155 poles’ dimensions – there were others, I did not miscount

My family took to the idea like a roasted duck to an orange sauce. Everyone was both excited and convinced I was kidding them, until she-who-must-be-obeyed greenlighted the purchase of 100 flimsy pipes at the eye-popping cost of 100 British monies. You should have seen the face of the delivery man who for the life of him could not imagine what anyone would want to do with that much garbage. It really is the cheapest stuff one can acquire without resorting to nefarious goings-on or actual miracles.

My philosophy is to avoid any actual work, and hence convinced my daughters of 12 and 14 tender years that they would be able to construct this affair with ease, and that It Would Be Quite Fun. The initial plan of simply assembling the whole thing and hoping the structure would hold itself together was quite naive, so we were forced to use small screws. This was a mixed blessing, but my dearly beloved offspring persevered, and after 20 hours of delighted labour the deed was done.

Well, at least the frame was up.

The whole affair was very much lastminute.com so not everything worked out quite as well as I hoped it would, in particular the schach (vegetation roof). Well, it still held up for the while festival, and seated 20 people in comfort, so who can complain?

The whole neighbourhood got to here about it as well, so we entertained approximately 500 visitors who wanted to eyeball the “climbing frame sukkah”.